Thirty-three years ago

April 14, 2012 | My Jottings

As I’ve mentioned before, over these last several months as we’ve packed things away and prepared (sometimes waffling from faith to uncertainty) to move to a smaller house, we’ve gone through old scrapbooks and reminisced.

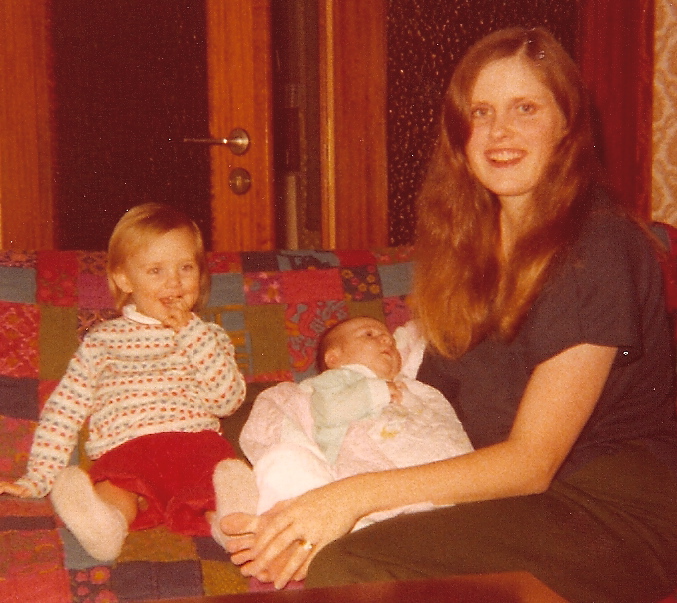

Here’s an old picture I found, of me (age 21), my oldest daughter Sharon (age 20 months), and my middle daughter Carolyn, who was a few days old in this shot. We were living in the beautiful little German village of Damflos. My husband, who was in the U. S. Air Force, worked in a top-secret underground military facility called the Börfink Bunker, from 7:00 a.m. until 7:00 p.m.

I loved Germany. Loved it. I loved being immersed into village life and having to bumble my way with the language, and I loved the castles and the forests. I was surprised to feel so at home so far away from home.

It took almost two months for our household goods to be shipped across the Atlantic to Bremerhaven in northern Germany, and then finally delivered to us in the western part of Germany near the Luxembourg border. During that time, with no radio, no television, no car, no friends, and only a very beginning grasp of the language, I reveled. I don’t know how else to put it.

I reveled in being a mom. Every morning I sat with Sharon on the floor and we played with wooden blocks with letters on them. At age 18 months she was holding up blocks and asking, “Whas dis?” I would answer, “That’s a D, and it says duh.” She would pick up another one and ask the same question, and as long as she was interested, I answered. She was reading fluently by the time she was 2 1/2, and I never pushed her. She still loves to learn today.

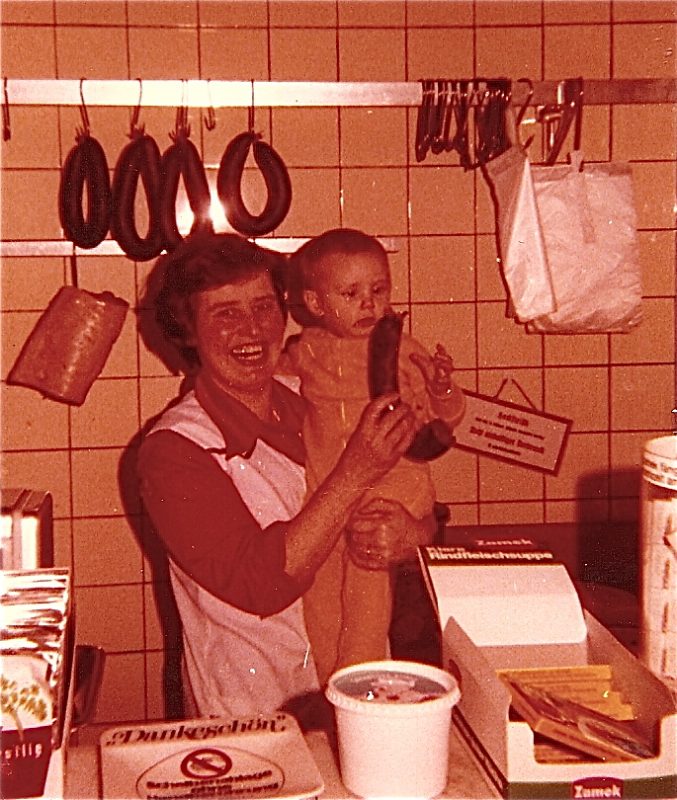

We strolled the streets of Damflos and noticed that the women bought their groceries every day. So many of them wore scarves, had very rosy cheeks, carried woven baskets over their arms, and dipped their heads and said “Tag!” to me as we passed on the street. First they’d stop at Edeka, a tiny little grocery-like store. Then they would walk across the street to the Beckerei, and come out with warm crusty loaves of dense bread. Then they would stop at our landlord’s butcher shop, called Metzgerei Diel. The shop was no larger than a small bedroom, with a long counter over a cooler, with hams and ropes of plump wursts hanging from hooks on the ceiling, and many kinds of rich meats behind the cooler glass that I’d never seen in the states. My husband loved sausage, I did not. But each time we paid our rent, Herr und Frau Diel would give us a large bag of various kinds of wursts that Herr Diel had made in the small barn-like slaughterhouse right behind their old, modest and immaculate home. There was deep maroon-colored blutwurst, fleischwurst, bratwurst, mettwurst, pig’s feet, pork cutlets dredged in a coating and covered with sliced onions, and massive slabs of bacon with tiny streaks of lean in it. I can remember it vividly. Chicken and beef made up a small percentage of what the Diels offered in their butcher shop; pork was the big deal.

Aloys and Anna Diel grew to be very precious to us. They knew we were young and thousands of miles from home, and they did all they could to make our stay in Germany a good one. They fell in love with “Bebe Scherren,” bought presents for her, held and kissed her, and crooned rapid, guttural German phrases to her that she quickly picked up.

They invited us to be part of their family Christmas celebration in their small living quarters upstairs from the Metzgerei. I spoke very broken German and the only English they knew was “Hallooo Yimmy Carter!” (President Carter visited Bonn while we were in Germany), but somehow we enjoyed each others’ company and were able to convey what was important. On Christmas Eve we sat in their simple parlor and watched them decorate their freshly cut tree, and in candlelight we sang Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht.

Here’s a photo of Frau Anna Diel with one year-old Sharon in the butcher shop. She wasn’t keen on Blutwurst either.

Here’s a photo of Frau Anna Diel with one year-old Sharon in the butcher shop. She wasn’t keen on Blutwurst either.

We lived in the Diel’s rental home, a newer two bedroom house right on their property, just behind their garage and slaughterhouse/barn. After we had gotten settled in, Frau Diel came over to visit and to instruct me (in German, of course, and with much pantomiming) on all that was expected of me as a citizen of the village.

The Germans are clean, organized people. The Diels wanted me to be clean and organized too. I don’t think I was too bad at it — I like order and did a fair job keeping things neat. But I was shocked when I looked in my German/English dictionary and it dawned on me that the words she kept saying to me, Fenster waschen jede Samstag, meant that she expected me to wash the windows every Saturday. “Jede Samstag?” I asked. She nodded vigorously and smiled, “Ja! Ja, jede Samstag!”

Frau Diel brought me a little red jug with a skull and crossbones on it (I am not making this up) and demonstrated how to pour one tiny splash of the clear, slightly thick solution it held into a bucket full of very hot water, and swirl it around with my bare fingers. She showed me how to dip a clean leather chamois cloth into the liquid with lung-burning fumes, quickly swipe the windows inside and out (thank God they were hinged and could easily swing open so I could wash the outsides), and leave the wetness to dry to a sparkly, perfectly streak-free finish. We’re talking just a few seconds of wiping. And that poison, whatever it was, made window washing a breeze and Windex look like baby saliva in its effectiveness.

I can handle this, I thought. I can wash the windows every Saturday. But then Frau Diel took me by the hand to lead me to the front of the house. She then began to show me in charades-fashion that also every Saturday, I would have to scrub the huge marble front porch which spanned the whole length of the front of the house, and the steps. She got down on her hands and knees to show me how easily I could look just like a washer woman and stick my butt up in the air for all of Damflos to see while I was scrubbing and wringing and crawling around.

Then, Frau Diel showed me where a witch’s broom was kept in a corner of the little garage. I say witch’s broom because it was a bunch of very long and sturdy, skinny branches and twigs, bound tightly together by wire, sans handle, and she led me to the curb at the front of the house and showed me how I would have to sweep the street free of dust, pebbles, rocks and any other matter…jede Samstag. The street. Every Saturday.

“Every Saturday I am supposed to do this?” I asked. More smiles and vigorous nodding; it was clear that my quick grasp of her instructions filled her with deep joy. I smiled weakly back and nodded, and gave an oh-my-gosh-help-me look to my husband who was watching us with raised eyebrows from the window.

So, like a good twenty-one year-old housewife and grateful guest of Germany, I did it all. I washed my windows every Saturday and scrubbed the continent-sized front porch on my hands and knees with my butt in the air and my pregnant belly serving as ballast, and I did the steps too. I took my witch’s broom out to the street and swept away every pebble from one end of the property line to another, and so did all the other German women of the village. We’d wave and call “Guten morgen!” to each other, and I knew they were probably nodding in approval. Maybe somehow I was making up for some of the American G.I.s who had wormed their way into German hearts by getting drunk on Heineken and peeing in meticulous German flower gardens.

My second daughter Carolyn was born in Germany, and Herr und Frau Diel fell in love with her too. They didn’t have grandchildren then, and I think they poured all their pent-up grandparental love out over my two little girls. And it was quite mutual. We all grew to love the Diels like they were our own family, and as my German improved we spent at least an hour a day together. They spoke to me about matters close to their hearts, and generously made our little family part of theirs. They even allowed me to ask them questions about the Holocaust and what they remembered about it. Frau Diel remembered being a little girl when Hitler came to power, and questioning her mother when the shops owned by Jews in the neighboring village of Hermeskeil were suddenly closed and boarded up. She remembered her mother shushing her when such things began to happen more often, discouraging her curiosity. The Diels told me that they did not believe until years later than millions of Jews had been killed; they had been told they were only deported. Early on they were happy with Hitler because they said he changed everything for the better — jobs materialized, the economy improved, and finally women were safe to walk the streets. Herr und Frau Diel spoke sparingly about it, and shook their heads slowly and looked down now and again, as if still trying to process that this had happened in their country, in their lifetime.

After living in Germany for two of our assigned three years, our world turned upside down. My Air Force husband met another Air Force wife at the underground bunker where they worked, and decided she was the one for him, baby. She left her Air Force husband, my Air Force husband left me, and it was quite the scandal in our little military community at that time. I was undone, but I had a two year-old and a nine month-old to love and care for, so I saved my tears until I went to bed at night.

I grieved the end of my marriage, occasionally gave myself an inner smacking for ignoring the giant red flags that were waving in front of my nose before I got married, wept for my children, and wondered how in the world we were going to survive. And as I packed and prepared the three of us to fly home to California, a trip that was to take a full twenty-four hours of travel and layover time, I cried over leaving Germany. And the Diels. They cried with me and shook their heads in sorrow over a young man who could throw so much away. And I don’t mean that I was such a treasure, I mean his two little daughters.

My husband eventually married the woman he left me for, but their marriage didn’t last. Over the next couple of years they both called me at various times and told me how the other had really behaved badly and hurt their feelings. I look back now and marvel that I didn’t start laughing maniacally at these calls. No, I just listened, wished them well, and hung up the phone.

You’d think that Germany would be a place of terrible memories for me, and that I wouldn’t recall it so fondly, but that’s not the way it is. In the midst of all that Sharon, Carolyn and I went through while we were there, I still smile when I think of Aloys und Anna Diel. A comforting kaleidoscope of memories forms; ruddy cheeks pressing up against infant cheeks, guttural German words turning a little softer when helping a blonde toddler draw a cat on a piece of paper, a thick German finger dipped into a bucket of foamy, maroon blood with a mischievous grin and a “Mmmmm, schmekt gut!” as Herr Diel chuckled to see my disgusted reaction, going to church on Christmas Eve to meet Saint Nickolaus and watching my little girls reverently take the fruit he gave them, walking through the clean streets of Damflos and wanting to pinch myself because I was living in such a beautiful, old country, picnicking in castle ruins, visiting Bavaria and staring up at the Zugspitze in awe, and reveling in it all.

After I returned to the states, for several years the Diels and I kept in touch. They wrote a letter a year which had to be translated by my German-speaking friend Bob. I wrote them once a year and they had a young man from their village read it to them. They sent a ham once at Christmas. We called each other a few times (I still remember their phone number) and I groped around with what few German words remained in my mind, and always we said, “Ich liebe dich!” I love you. They sent pictures of their two pretty, rosy-cheeked granddaughters. Then Herr Diel died, and gradually I stopped hearing from Frau Diel, and then over time I stopped writing.

I still think of them, though. I think of how privileged we were to be immersed in German village life, and to be welcomed, taught and loved so generously by the delightful couple who owned the little butcher shop in Damflos.

Oh what a lovely post Julie! I really enjoyed reading it and how you took the positive out of a situation where so many foreigners wouldn’t have. I couldn’t agree more about the Blutwurst though!

I changed the spelling of Bludwurst to Blutwurst after your comment, Helen – thank you! I’ll bet you have had a few experiences calling for patience and adjustments as well, moving from England to America to Switzerland! Have a good weekend….

You were, and remain, amazingly resilient Julie. And it seems you have always been able to be aware and considerate of others—with faithfulness and generosity. It seems your love and dedication to your lovely daughters played a large part in providing you with the grace that brought you all through times that, I know, would have torn others to pieces.

Roberta, if I am resilient it is because of God’s help. I’m really a bit of a wimp. There’s something about having little children that keeps people putting one foot in front of the other – they were my motivation to keep going during those hard days. God bless you….

I think you and Dad should try to take a trip back there!

We would love that!

I enjoyed your post on Germany and it also brought many memories back to me as well. When I went into the service in April of 1964 the Nam war was going strong and I was eager and proud of the country I was born in. I signed up for duty in Nam and also for airborne. About 7/8 through boot camp, I got conformation that I would be going overseas and that I would be going to fort brag to be come a member of the 82 airborne division.

When it came time for me to go from boot camp, to advanced infantry training something happened and I still to this day do not know what happened but I was put on hold with three other men and was told that my orders were coming. For two weeks I cleaned empty barracks and folded blankets and sheets for the post to be ready for the next bunch of would be troops to rotate through.

I had been pretty good at physical hand to hand during boot camp and it ended up being a blessing for me even though I did not think so at the time.

When my orders did come in, I was informed that I was going to have a MOS as a airborne field medic and would be heading for San Antionio Texas for my medical training that after that I would proceed to brag for jump school.

I finished medical training and again I had a wait. But this time I was ask if I would be willing to consider taking a position of personal body guard for field officers

I felt it would be unusal to be in Nam and be a body guard, and I said yes.

I ended up being a body guard for a battalion commander. He went to Nam for three days than was transferred to Germany, at Stugart. I think I am spelling that correctly as it has been a long time.

It was a hidden blessing in all ways. I never worked my trained MOS but also did not ever work very many days in any one week. The Old Man as we referred to other about him was not required to do much outside a war zone, which Germany was.

My friends became those who served him like I did, his driver, his com man and his officer go-fer and his sargent shoe shinner.

I became close to the old man and Kutchie his driver and Smart his com man became like his family.

Each day when he did work or come on post two of us would go to town and bring him on to the post as he did not reside on post.

He was a heavy drinker and I think that war can sometimes bring out the worst in a person or the best? He was in Nam before but i never got to see what he was like in a war zone.

When he drank late at night, we would get a call to go pick him up were ever he ended up and take him to his house.

It got to a point that he only worked two or three days a week, so the three of us, Kutchie, Smart and myself started taking trips to see Europe. I purchased a new VW and we went all over Germany, it seems strange that after all these years, I now learn where you were located while you were there, I never stopped there, but passed through – I do not know how many times. I loved looking at the homes, the rounded rock narrow little streets and the country side.

I too have many memories that were all good of the people that lived and grew up there in Germany.

I learned a lot I didn’t know here, Lar. Thank you for sharing…. We only drove through Stuttgart when we were there. I sure remember the blue Volkswagen you brought back from Germany too. xxoo

Dear Julie~

This blog made me smile but I also wanted to cry because of your loss ~husband, beloved Germany and your dear German neighbors! My Maternal Great Great Grandfather was from Germany~ Nicholas Regielspurger. He was from the Black Forest. I took one year of German in High School. I visited Germany briefly on a tour of Europe spending time in Cologne and a little of the Black Forest, I was so close to the town where my family came from, so close, but yet so far! Thanks for sharing…………..Susan

Thank you for your comments, Susan! I was in Cologne as well, but the Black Forest was one of my favorite areas… God bless your week!